Friday, March 14, 2014

Tomorrow Never Knows

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

Here, There, And Everywhere

Richard Furnstein: A shimmering beauty. It's certainly up there with (its point of inspiration) "God Only Knows" as The Greatest Love Song In World History. Both songs share a similar quality of being at once complex and simple, although Tony Asher's lyrics for "God Only Knows" aim for a much deeper sentiment than "Here, There, And Everywhere."

Anyway, we're lucky that Paul McCartney plucked this song from the heavenly clouds of eternal genius when he did because the Revolver-era Beatles were particularly well suited to record this track. A swell of harmonies raise a glowing banner over the opening lines, before Ringo's gentle cracking leads us into a comforting chord sequence. Paul casts some shadows with a well place F#m ("wave of her hand") before settling back into a comforting tin-pan alley stroll. The performance is a lovely demonstration of restraint. Just listen to the crackle of John's bad boy rhythm guitar and George's sugar glider guitar leads. And then, all of a sudden, the "perfectly lovely" tune accelerates on the milky mile and blasts through the galaxy (right at the moment of "I want her everywhere") as Paul expertly changes key and mood. John and Paul would regularly claim they were just uneducated brutes taking a stab at writing some tunes, as if it was all about stealing some girl group melodies and throwing in some joker chords. That chorus isn't the work of some dumb cavemen, it's pure wonder.

Robert Bunter: Paul's love songs often take the long view - where John tended to be galvanized or tortured by the intense emotions of the immediate present, Paul often seemed to look ahead to the years of gentle mornings, quiet afternoons and tranquil evenings which are the lifestuff of a loving married couple. With John, it was all or nothing - he was in your face, screaming "Help!" or "You better run for your life!" or "I want you so bad it's driving me mad." Paul played it slow and steady, longing for a mellow partner with which he could live on a farm and smoke reefers with. "Here There And Everywhere" fits this template, along with "And I Love Her," "I Will," "When I'm 64," "Every Night," "Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da" and many others. Later he found that wonderful mellow reefer woman and they spent many happy years together. Meanwhile, John married a crazy artist and spent the '70s lurching from one ridiculous obsession to another (radical left-wing politics, conceptual art installations, drunken party animalism with Nilsson and Ringo) before finally settling on the "stay at home and quietly bake a loaf of bread" plan that Paul was advocating all along. Or so it seemed to the outside world. Unfortunately that's not really how it was. John spent those late '70s post-Walls and Bridges years in an opiated stupor, his body wasting away to nothing and his once-sharp mind reduced to the floppy texture of an over-boiled noodle. Meanwhile Yoko was consulting a series of astrologers and wasting huge amounts of money. I'm sorry, these are the facts.

Richard Furnstein: Hey man, I wish it wasn't true. John was unfortunately constantly searching for a way to fill his empty heart with life. Lennon's wanderlust combined with his (underdeveloped) political concepts and yearbook-yearning poetic musings capture the imagines of the sensitive and troubled. John wanted love (or, more accurately, to a mother's love) while the world presented him endless opportunities to live out Freddie Lennon's most reckless seaman fantasies. Meanwhile, Paul was similarly pushing towards the light, but found greater comfort in melody, emotional directness, and (you are absolutely right) domestic tranquility. Paul's steady hand would later be exposed as his greatest weakness in the band (his propensity for "granny music" late in The Beatles and throughout much of Wings). I'm certainly not the first to point out the fundamental differences in the Lennon/McCartney songwriting team. Consider for a second that Paul tried to bring emotional security to the neglected Julian Lennon during his parents' divorce in "Hey Jude" while John delivered a rattled and politically confused "Revolution" as the b-side. "Here, There, And Everywhere" can be similarly viewed as a peace offering, a guide to adulthood that takes a different form than John's sloganeering or George's green mysticism.

Richard Furnstein: The stripped down nature of the song provides all the glitter that this song needs. The swelling ocean implied in Ringo's rich cymbal hit is absolutely perfect. The guitars provide some lovely and unexpected textures, including the bright push of tiny amplifier tubes as well as the ambient creaking wood and fret noise that runs throughout the song. I particularly want to call out John's somnambulist "love never dies" and "watching their eyes" at 1:55." It's all too much.

Robert Bunter: The whole thing sounds as warm and lovely as a bright morning with the lovely Linda on the McCartney's ramshackle Scottish farm in 1971. A cup of tea and a cigarette; read the latest issue of the Melody Maker while Linda boils an egg. Later: vigorous physical lovemaking and an hour or two at the piano searching for melodies. These are the days of our lives.

Friday, May 11, 2012

I Want To Tell You

Richard Furnstein: This is the part where I tell you that you are completely wrong, right? WRONG. You are actually right. I've always considered "I Want To Tell You" one of the purest and most beautiful Beatles songs. It suggests an age of discovery that is rooted in bubblegum while hinting at the weirdness and ambition that would catapult The Beatles past mere saccharine treats. I imagine super intelligent aliens would produce something similar to "I Want To Tell You" if you gave them a copy of a 1910 Fruitgum Company album and some gentle early-generation drugs. As you said, it was such an incredible accomplishment for George Harrison at that stage. It's only a year removed from such awkward fare as "I Need You" and "You Like Me Too Much," yet the quality of his Harrison's Revolver material suggests a complete reevaluation of his songwriting contributions to The Beatles. "I Want To Tell You" is the best of the bunch and never sounds like a gangly younger brother of John and Paul's muscle man songs. I honestly don't know if either of them could come up with a song that so perfectly balances innocence and tension.

Robert Bunter: It’s just exciting, man. This song has an irresistible energy and drive. For once, George’s thick, phlegmy Liverpool accent is perfectly suited to the music. Major buddies John and Paul chime in on wonderful harmonies, of course. Can you imagine how good the guitar solo would have been, if there was one? The lyrics evoke the world of emotions that George was likely feeling during this heady time. Sure, there were countless meaningless groupie conquests and late-night snogs at the Bag O’ Nails club, but in the swirl there may have been a few young ladies who inspired real feelings in this sensitive young man. His fast-paced world didn’t allow their full expression, however. Picture it: Stockholm. 1965. George slowly awakens, looking slim and fit in his fashionable “Swinging London” undertrousers. Last night’s “bird” slumbers gracefully beside him. Gerte (or was it Fabiene?) had some surprisingly complex thoughts on Dylan’s latest LP, and her hair had that great smell that you only get to smell once in a while. Of course, she was stunningly beautiful. They laughed all night, and when she smiled it lit up the whole room. But now it’s 6:45 a.m. and the cold grey dawn is seeping into the windows of this luxury Stockholm hotel. “Eppy” (dapper Beatles manager Brian Epstein) is on the phone and it’ll soon be time to catch the limo to the airport. The horrible shrieking of thousands of kids outside is already audible. Jesus, I don’t even have time to brush my teeth. What was her name again? “I’ll probably never see her again,” George thinks to himself, and he was right. Later that afternoon on the private airplane, George stares out the window, lost in melancholy thought as the other Beatles laugh uproariously in the course of a card game. Mal Evans is wearing a cowboy hat and everybody’s listening to Herman and the Hermits 45’s at the wrong speed. Now that you’re inside George’s headspace, put “I Want To Tell You” on again and you’ll know exactly where he was coming from. That’s the true story of how it happened.

Richard Furnstein: Thank you for that. I pictured it. I went online and went to cvs.com and printed it at my local pharmacy. I'll probably frame it later if I stop by Ikea this weekend. I truly want to believe that the genius of "I Want To Tell You" came from pure inspiration--a hint of French perfume on his wrinkly collar--rather than a blind hit from George Harrison. It really does succeed in many areas where George's songs usually fall flat. You already mentioned the appeal of his phlegmy voice on this track--an anchor on many Harrison songs, especially in his 1970s solo output. The bridge is a particularly interesting case: it's a really unique progression. Typically, George's explorations in non-conventional chord structures sound a bit stilted and overly melancholy (put on the Living In The Material World album for evidence). Finally, George slips some of his Eastern-melodic influences on the songs outro ("I've got tiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiime"), giving the song a hint of Champa without completely falling into the Pagladiya River ("Within You Without You" and "The Inner Light"). To be fair, those perilous and perfect undulations sound like they are coming from Paul's golden throat (Paululations!). "I Want To Tell You" is truly George Harrison's perfect game. It's a beautiful thing and it's thrilling as can be, but you almost wonder how the heck he pulled it off!

Robert Bunter: You’re correct. Let me just take this opportunity to say, was there ever a better drummer than Ringo? His lead-footed beat and primal fills are absolutely crucial to this track. Paul’s bass is wonderful, especially toward the end where the whole thing starts to unravel. John’s contributions are less clear – I’m sure the cleanly picked guitar arpeggios were George’s work, and Paul seems to be the main presence in the vocal harmony mix. I imagine John might have been sitting up there in the control room, with a slightly raised eyebrow as he listened to the initial takes, like “Oh ho? Wot have we here? Thick little George has written quite a good track here, hasn’t he? Perhaps I need to step up my game.” That’s just a little imaginative flight of fancy, I have no way of knowing whether that ever really happened. I’m sure John Lennon never thought or said the phrase “step up my game,” for one thing. But I know this: my earlier fantasy about George and the girl in Stockholm is completely true. It just has that ring of authenticity to it.

Richard Furnstein: Huh, what? Sorry, I zoned out there for a minute. I was too busy imagining myself in that Stockholm lovers' nest. The morning damp with regret. Heart strings pulled by the stern hands of Grandfather Time. It's a sad and beautiful story and I wish I had the bed sheets for my special Beatles memento collection.

Friday, April 13, 2012

Got To Get You Into My Life

Robert Bunter: Huh? What’s that? You’ll have to excuse me, I was just picking my face up from the floor because it’s been blasted off by this high-powered Beatles track. Whoo-whee. SHAKE IT! Let’s talk about album sequencing – this would have made a fantastic opening track for Revolver, with its expectant mood and surging exuberance. Any other band would have done that, but, characteristically, the Beatles had a better idea. By placing “Got To Get You Into My Life” second-to-last on side two of what has already been an astonishingly brilliant album, they create the surprising impression that the record is actually gaining new momentum as it nears the finish line. Then, of course, they up the ante dramatically with “Tomorrow Never Knows.” Game over. Revolver is a microcosm of the exponential development arc of the Beatles’ pre-White Album career. It starts out great, then it just gets better and better and better. Better than you ever could have dreamed. Then, all of a sudden, it gets 500 times better than that. Hyperbole? THAT’S AN UNDERSTATEMENT.

Richard Furnstein: You're not wrong! Listen, "Got To Get You Into My Life" is a top ten song. "But The Beatles have a ton of great songs, Richard. How can you say that?" Listen, man. I'm not talking top ten Beatles, I'm talking top ten all time. I couldn't tell you if it's about drugs or love or sunshine, but I can tell you that hearing this song is as close as we humans will come to actually levitating. I'm talking gliding down the sidewalks like in a classic Spike Lee trolley shot, the gladiolas blur past our faces stunned in bliss. Are we heading towards the sun? Of course we are. Good Lord, there may be two suns in the sky. Anything is possible right now.

Robert Bunter: Did you hear McCartney on Fresh Air the other week? Terry asks him if he felt concerned about notions of authenticity when they were young, white English kids attempting to play American rock and R & B. Paul says something like, “We weren’t sophisticated enough to worry about stuff like that, we just thought it was fun to have a go. We knew we couldn’t compete with the masters.” That’s exactly the point: American music styles (in this case, Motown/Stax) were just more dabs of paint on the palette. They could plunder and appropriate genres for their strengths, without feeling any need to prove their authenticity. British artists who didn’t learn from this wise example fell flat on their faces. Listen to Eric Burdon’s putrid bellowing or the flatulence of Alvin Lee “singing the blues” and try not to barf.

Richard Furnstein: The difference is that The Beatles would root their genre explorations in actual songs, rather than just hairy chested moon howls over a blues dirge or damp noodle bellows over flute escapades. With that in mind, "Got To Get You Into My Life" is actually a pretty light song for McCartney. The demo version from Anthology exposes the delicate underpinnings of the song, an organ drone and some rough background vocals. This early version highlights the strength of the horn section and George Martin's arrangement. The Revolver alternate takes are the highlight of the Anthology discs, and "Got To Get You Into My Life" is the best of the bunch. It's almost a completely different song in its naked state, revealing the incredible creativity at this phase. It's what I like to call "the departure point."

Robert Bunter: Yeah, I just listened back to that version, too. One of the things that struck me was the Eastern-sounding harmonies of John and George’s backup vocal parts (first appearance at :43). There are some very similar moments of non-Western diatonic dislocation in the vocal tracks of “I Want To Tell You” (during the fade), “Love You To” (“You don’t get time / to hang a sign / on meeeeeeeeeeeee”), McCartney’s “Taxman” guitar solo and it’s backwards reappearance in “Tomorrow Never Knows.” I must say, in the case of “Got To Get You Into My Life,” I wish they’d left them in. It was a nice, freaky motif for the album. Leave it to the Beatles to take something as unappealing as moaning, dissonant backup vocals and turn it into a glorious asset. One point of disagreement: “Got To Get You Into My Life” is the best of the Anthology Revolver outtakes? How unfortunate that your defective copy does not include the happy giggle version of “And Your Bird Can Sing,” which is universally acknowledged as such.

Richard Furnstein: The giggle take is fun, but life isn't a slumber party goof fest. You would certainly rejoice at the altar of EMI if they released the 27 minute version of "Helter Skelter" with Mal Evans making fart noises over top.

Robert Bunter: “You’re not wrong!”

Thursday, February 23, 2012

Doctor Robert

Richard Furnstein: Strong but fair. Sure, we all want to freeze those Revolver Beatles in time. They still wore suits when Brian Epstein told them to, John still had his baby fat, and they all played on the records. It was a beautiful time. And, sure, "Doctor Robert" would have been a nifty lost track to accompany this little playground of the mind. Well, roll over, Beethoven. The Beatles gave us "Rain" as the b-side of this era. A b-side that was set down on a golden marble pedestal by angelic unicorns in a hailstorm of first kisses. I ain't complaining and I'm not playing God. I'll take it. Give me one "Doctor Robert," barkeep. There's some dust on that bottle but it tastes mighty fine.

Robert Bunter: John's head was spinning and his pupils were dilated, so he wrote this funky ode to a mythical, drug-dispensing Dr. Feelgood. It's got a creepy feeling to it. The angelic "Well well well / you're feeling fine" chant has a vague undertone of menace. The lyrics are cryptical riddles, delivered in an odd rhythmic meter, with strange chord progressions and shiny guitar tones. At the very end as it fades out, it goes to a chord that didn't happen in any of the earlier choruses. Vintage Lennon. Great stuff, man. Great stuff.

Richard Furnstein: "Doctor Robert" is another case of The Beatles providing a glimpse into their drugged out, finely tailored lives. As John and Paul moved away from love songs, they found greater inspiration in the small moments in lives and the odd characters that filled their protected lives. Doctor Robert was just another of these faceless humans, paper cut-outs of humans that entered into their lonely orbits. The shadows dominate much of their songs from this period and later. Eleanor Rigby is a lonely old maid, a symbol of their yearning for understanding. The "bird" from "Norwegian Wood" is so vividly sketched that you can imagine the long brown hairs danging from her hairbrush at the end of the bath. Bungalow Bill has a hell of a smile. You get the picture, or maybe you don't (and isn't that the point?). The Beatles had to make sense of these lesser humans that entered their lives. You always got the sense that Paul thrived on his sketches of humanity ("Another Day" is one of the greatest examples of his "oh life" songs) and John dipped his toes into the waters a bit before going full oninto self exploration. "Doctor Robert" is the ultimate soulless character from their songs. He's a side effect of celebrity, the kind of unseemly and sinister character that The Rolling Stones loved to throw into songs. The good doctor is the late night visitor after an evening of the nightclubbing in A Hard Day's Night. "This will calm your heart, Johnny. You have to get on a plane in the morning!"

Robert Bunter: You've got a point there. As we've done so many times before, it's useful to imagine the impact this track had on the impressionable young listener. Whether it was a callow young lad who looked up to the cheeky moptops as life inspirations or a young tinybopper who wanted Ringo to ask her to the sub-junior ring dance, they were surely shocked when the bouncy love songs of yesterday (!) gave way to Revolver's creepy character portraits, incomprehensible acid invocations and complaints about her majesty's marginal tax rates on top income brackets. John's lyrics on "Dr. Robert" are delivered like the sales pitch of some shady character in an alley, holding open one side of his oversized trenchcoat to reveal a selection of illicit wares attached to the inner lining. "Pssst, hey kid, c'mere. Try this." John would return to this mode with the terrifying carnival barker of "Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite," the belligerent interrogator of "I Am The Walrus, "Hey Bulldog," "Glass Onion," and the leering pervert of "Happiness Is A Warm Gun." When John wasn't analyzing his own tortured psyche, he seemed to get a kick out of directly addressing you, the listener, with unsettling, one-sided conversations. Even when he tried to play the Paul role (third-person narratives about colorful characters), he couldn't seem to help himself from wallowing in the imbalanced power dynamic between artist and consumer. The John-Figure stares out at us from the black vinyl grooves with bared teeth and uncomfortable eyes.

Friday, November 18, 2011

Yellow Submarine

George Martin did his best to cover up the corpse stink on the dreadful basic track, dumping lots of woooshing sounds, British jibberish, and klaps and flaps and torts.

Robert Bunter: Ha! You fell for it again. Hey, your fly is down. Whoop! Made you look. Got your nose! It’s so easy to get your goat, you should hang a “free goat available” sign outside your home. OK, fun’s over. Let’s get down to business. “Yellow Submarine” is a drag, but you have to admit, the animated cartoon feature which it inspired was a truly joyful psychedelic romp. Also, the “Eleanor Rigby / Yellow Submarine” single is a fine example of the striking contrasts they deployed to such great effect (“Strawberry Fields” b/w “Penny Lane,” “Lady Madonna” b/w “The Inner Light.”) From the sublime to the ridiculous; fun for the kiddies, the dawning of a new growth. Beautiful!

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

She Said She Said

Richard Furnstein: There are three moments of this song to live in. First, the recording session with Admiral Pinwheeleyes dictating the waltz bridge to his less zonked companions. I think you nailed that one, old friend. Second, the moment that the shaggy headed youth first heard this song, revealing a world of fear and chaos and gruesome discovery. They were just catching up with the playful marijuana games ("Hey Todd, play back that part on "Girl" again, is John smoking a jay?") and now Lennon removes the mountains, trees, and gentle deer from the landscape. It's all been replaced by a terrifying abyss where orange smoke plays the role of furniture, castles that house the wandering dead yawn out of the bubbling ground, and a series of malevolent fauns are at play in the whispering dew. Things have changed, Todd. It's brutal underground after you die. All you have is your mind to keep you company as your mouth fills with dirt. You know what the third moment is?

Robert Bunter: Of course I do, dummy. It's the party where this song was born (or was it? Get it?). Cast your mind back to Los Angeles, 1965. It's a brief break from the endless touring; they've rented a lovely house with a pool and filled it with semi-celebrities and gorgeous women with whom they do it, over and over again. John and George just had their first acid experience a few weeks ago, when they were unknowingly dosed by a horny dentist who wanted to drill Cynthia and Patti. Now they bought their own, and they're ready to try it again. Paul's not ready, but Ringo's more than game.

It's brutal underground after you die. All you have is your mind to keep you company as your mouth fills with dirt.

Richard Furnstein: Yeah, but Ringo's a lightweight. He takes a dose and then wanders off from the party a few times. He's redirected by the police, and is found later passed out behind a drum set in the basement. John's on cloud nine, though. It's the first time that his brain seems on center with everyone else. David Crosby's smiling eyes wander into his brain as they discuss Shunryu Suzuki and Norwegian women. It's a meaningful fix, like a helix fornicating with a three headed snake. Peter Fonda wanders up and gives new meaning to get your motor running and heading out on the highway. The motor is your psychological fears and the highway is psychotheraputic explorations of the inner spirit.

Robert Bunter: Fonda's not exactly a mental heavyweight himself, if you acquire my drift. So the drug takes a turn in his brain and he starts remembering the time he accidentally shot himself as a kid. He becomes fixated and starts mumbling about "I know what it's like to be dead." John tells him to bugger off, but it's too late. Once an idea like that gets into your acid trip, the fun is over. You may as well just head inside and try to have some dinner. The problem is, you're too confused from the drug to operate your knife and fork correctly, so you end up spilling all your food onto the floor. What a bummer. It's all you can do to drag yourself upstairs and do it with another three Playboy girls before going to sleep. Meanwhile, Peter Fonda is puking into the fireplace after he tried to eat the food you spilled on the floor. We're not in Kansas anymore. This is late August, 1965 at 2850 Benedict Canyon Drive in Beverly Hills. If you invent a time machine and go back there, be cool. Don't disturb the Beatles with your dumb obsessions. I'm certain that if it had been me, I would have behaved in an appropriate manner.

Richard Furnstein: Is there a better use of a time machine than to head to that Beverly Hills home on that historic day? I'd play it cool as well. Maybe a dip in the pool (proper swimming attire optional!), eat some snacks (I am thinking fancy cheeses and salted pea pods), and thumb through their magazines. I'd be careful not to drastically impact the continuum of reality. Sure, I'd like to get in on that conversation with Pete and John, but I'd hate to throw John's creative drive off track. I would never forgive myself if "She Said She Said" didn't end side one of Revolver!

Robert Bunter: Oh man!

Monday, August 29, 2011

And Your Bird Can Sing

Richard Furnstein: Good almighty, put on the mono version right now. Paul's bass is like a locomotive, tearing through boring British homes. He's exposing the pipes, you see Uncle Corky eating his crisps with tea. It's all over. Hey mankind, your dream was boring and inadequate and John and Paul wrote a new script and it rules so get in line or die. This is the future, man.

Robert Bunter: Beatles are the best band. Revolver is the best record. "And Your Bird Can Sing" is the best song. The blog is over. From here on in, it's all downhill and writeups about the Marvelettes covers on side nine of the Beatles At The Beeb bootleg box. Do I really have to dissect this wondrous thing? OK - the band is firing on all cylinders. The guitars are blasting out electric harmony parts while Ringo flogs the topside of the Ludwig ThunderTubs. Paul's bass is a locomotive, as you correctly noted. George's solo recontextualizes the universe of critical possibilities into new and compulsive color-shards. John and Paul sing harmonies that just make you want to die. And John's lyric uses the full power of his linguistic inventiveness and psychedelic flights of fancy. On paper, it's gibberish, but when you hear it sung (turn it up, man, turn it up!), the meaning(s?) is (are?) crystal clear. He's being accusatory, smug, self-assured, enigmatic, yet the whole thing is undeniably joyous. Get with the program.

Richard Furnstein: You are correct, my oldest friend. I don't tell you often enough, but I love you. To me, "Bird Can Sing" is one of The Beatles' under analyzed "reflections of rich dudes" songs. It's an elite group that includes gems like "Can't Buy Me Love," "Baby You're A Rich Man," "All You Need Is Love," and most of George's reflective material. The Beatles knew they were the hottest poop in the universe and were rich to boot. They slowly start to realize that there is more out there than cash, sleeping with Joan Baez, and wearing really cool clothes. There was love out there and peace and understand and curry. John seems to be singing to his fellow rich men who have it all, including a "bird that can sing." Hello, Marianne Faithfull. Come right in, Linda Eastman. We've been expecting you, Yoko Ono. Yes, the adolescent minds in The Beatles are simultaneously trying to expand (cue the sitars) while staying true to their schoolboy purpose (cue Chuck Berry lick). Girls? Shit, they can join the band. Get in the booth, honey. What can possibly go wrong? It's such an innocent idea that foreshadows the increasing rift as Yoko insisted on sitting next to John when he was in the toilet and Linda's father tried to get a slice of The Beatles' management pie.

Open a window, it smells like childhood pies.

Robert Bunter: Hmmm ... I never really considered your girls-joining-the-band angle, although there's enough ambiguity here for many interpretations. I always heard the lyric as a Dylanesque put-down of a poor little rich girl who thinks she's Miss Sand but doesn't really know where it's at, like "Queen Jane Approximately" for example. But, you know the old trick of lyric analysis: you just turn it around. "Sure, Dylan was writing a series of withering insults about the fools that he saw everywhere he looked. But, really, on a deeper level, wasn't he really writing about ... HIMSELF?!" Viewed from this angle, I can get behind your "reflections of a rich dude" angle. Lennon's prize possessions (deluxe Vox organ stand, mahogany bookcase, colorful Rolls-Royce, rare art collection, novelty gag gifts) are really weighing him down. "You may be awoken / I'll be round," actually the voice of Yoko, singing to and through John from the future? It's not outside the realm of possibility.

Richard Furnstein: Exactly. Who will be awoken? And when? And how? Cue sitars. It's an exciting prospect: John Lennon, on the edge of "Strawberry Fields" and "A Day In The Life," considering the effects of his mind on the world (and possibly himself, consider the upcoming acid madness of Syd Barrett). It's the brash and dramatic dealings of an insecure genius, and we're still trying to catch up.

The resulting track is perhaps the band's most perfect recording. And this time I think I'm right.

Robert Bunter: You're not going to get any argument from me about that one. Now we're just waiting for the other shoe to drop. I'll give you a hint: it's old and brown.

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

I'm Only Sleeping

Richard Furnstein: Notorious lazy bones John Ono Winston Lennon continues his descent into self important "life-as-songwriting" with "I'm Only Sleeping." Using the template of "Help!," John writes what he knows (self-loathing and drug-induced stupors). It's a trick he would continue through the Sgt. Pepper era, only the promises of Eastern mysticism and Yoko Ono's progressive caterwauling would push Lennon's creative output to adopt the imagination displayed in his early short stories.

Richard Furnstein: Notorious lazy bones John Ono Winston Lennon continues his descent into self important "life-as-songwriting" with "I'm Only Sleeping." Using the template of "Help!," John writes what he knows (self-loathing and drug-induced stupors). It's a trick he would continue through the Sgt. Pepper era, only the promises of Eastern mysticism and Yoko Ono's progressive caterwauling would push Lennon's creative output to adopt the imagination displayed in his early short stories. We could all learn a thing or two from this overweight, emotionally-stunted drug abuser when it comes to things like how we should stay in bed all day, or how easy it is to ignore your wife and child.

Richard Furnstein: It's pretty neat that George Harrison, he of superior teeth and slightly above normal intelligence, managed to complete define the backwards guitar solo in this early man attempt at studio trickery. Imagine that: "Shall we flip the tape for the solo?" Sure, says George, then he continues to draw a map away from the treasure (pop music perfection) to the startpoint (coordinates that I like to call innovation and inspiration). And he draws the damned map in perfect handwriting. Listen to that guitar solo. Don't forget to hang onto your butts in the process!

Robert Bunter: This is a song that shows the influence of drugs. John is tired because he's spent most of the past five years running around like a lunatic, and also because he's smoking reefers every two seconds. He's just saying: hey, don't wake me up. But in a deeper sense, isn't he also criticising all of us as we scurry through our drab nine-to-five routines? We could all learn a thing or two from this overweight, emotionally-stunted drug abuser when it comes to things like how we should stay in bed all day, or how easy it is to ignore your wife and child. Later, he would write "Rain" which explains how dumb we are for trying not to get wet from the rain. He's just so advanced and we need to start taking the hint.

Richard Furnstein: I got a head start by napping during your verbose and confused interpretation of this pop song. Great job!

Friday, April 22, 2011

Good Day Sunshine

Richard Furnstein: I'm going to stop you right there because you sound like an idiot. Paul's checking in with a twirling vaudeville hat and playful cane. He's kicking off side two of Revolver the only way he knows how: with perfect pop that provides only a slight whiff of the drug abuse that runs loose on the rest of the album. The subversive twists are subtle on "Good Day Sunshine"--the slow motion distorted chug of the introduction, the key change (if this suggests mind alteration, then Barry Manilow may be Timothy Leary), and vocals that swirl around the listener like sweet opium birds. Paul would search for a similar vibe with later side two lead off hitters "Martha My Dear" and "Hello Goodbye" (please forgive me for referencing a Capitol tracklisting), a little saccharine to lead you through the inevitable end of album drug haze.

Robert Bunter: When you’re right, you’re right. This is the first time in the catalog that Paul did one of these old-timey shuffles. I can imagine John and George giving each other little sidelong glances as they stood at the microphone recording the fantastic vocal harmonies. “George, this is a little fruity.” “I think you’re quite right, John. Paul has written a fruity song.” Ringo just sat in the corner playing cards with Neil Aspinall, having finished his tracks two days ago. Astute fans will note that the seeds of the breakup were planted here. George was looking forward to going home and spending more time burning joss sticks, listening to his sarod records and getting fitted for a flowing pair of silk yoga briefs. John, meanwhile, just noticed that his ego is a plastic illusion and is still seeing “fish with heads” in the corners of his vision. Against this backdrop, Paul’s mildly-psychedelicized update of 1930’s music hall razzmatazz must have really grated.

Richard Furnstein: I beg to differ, I think Paul's first few forays into the fruit bowl were seen as deliciously subversive from the Ultimate Gang™. Delightful, even. A drop of purple windowpane into granny's tea. A nice dusting of opium on Auntie Minn's biscuits. Paul wanted to welcome the entire world into the expanse of drugs and love and rich blonde girls on summer lawns. You aren't going to catch the elusive old lady fish with "Dr. Robert" or "Rain," you have to throw them a bone to bring out their inner freaky deaky. Sure, Paul later took it too far (I'm sure John wanted to freeze Paul's bloomers when "Honey Pie" was being tracked) but he's decidedly on point here.

Friday, April 15, 2011

For No One

Robert Bunter: What a downer! Quite possibly the most unrelentingly sad track in the entire catalog ... well, maybe tied with "Eleanor Rigby." It's not sad in the gentle melancholy way of "In My Life" or the poignantly longing way of "You Never Give Me Your Money." It's just a stone bummer. Paul uses the Fabs' trademark personal pronouns ("She Loves You," etc.) to devastating effect. The whole thing is addressed directly to you, the listener. And you, the listener, are in sorry shape.

Robert Bunter: What a downer! Quite possibly the most unrelentingly sad track in the entire catalog ... well, maybe tied with "Eleanor Rigby." It's not sad in the gentle melancholy way of "In My Life" or the poignantly longing way of "You Never Give Me Your Money." It's just a stone bummer. Paul uses the Fabs' trademark personal pronouns ("She Loves You," etc.) to devastating effect. The whole thing is addressed directly to you, the listener. And you, the listener, are in sorry shape. Richard Furnstein: An economical weeper from Sir Paul. He gets right to the heart of the matter, describing the sun rising on a broken heart. Paul is more than comfortable telling a story in his songs, but he typically puts the spotlight on boring non-genius people going through their lives devoid of exotic drugs, beautiful blondes, and orgies with Peter Sellers (alleged). Paul keeps things nice and tight (and sad) in "For No One." His break-up songs on Rubber Soul find Paul stuck in the anger stage of acceptance ("You Won't See Me," "I'm Looking Through You"). "For No One" suggests his grief has moved on to depression and acceptance.

The feel of this one really brings me back to "Rigby" (acceptable shorthand in the Beatlemaniacal community). They both deliver some non-rock melancholy on Revolver (Paul's specialty from this period) while focusing on personal details and moments of reflection that speak more about the heartbreak than the early Beatles' focus on loving, leaving, and crying. The cause of the split doesn't matter to the songwriter, the isolation is the selling point here.

Robert Bunter: The song serves as an unsettling grey detour from the otherwise thrilling, ecstatic emotional rocket ride that is side two of Revolver. "Good Day Sunshine" celebrates a nice day with childlike glee; "And Your Bird Can Sing" makes a joyful psychedelic noise ... then, all of a sudden you find yourself waking up with a headache, pondering a girl who not only doesn't love you anymore but doesn't even care. It's like a bucket of cold water over your head. Don't worry, though. You'll surely be cheered up by "Dr. Robert" and his drugs. Then there's "I Want To Tell You," which is suffused with such infectious joy, it leaps right out of the speakers. Then "Got To Get You Into My Life," which does the same thing times fifty million, and finally we end up dazed in the blissful acid ecstasy of "Tomorrow Never Knows". But as you float downstream in the egoless glow of pure consciousness, it's hard not to be haunted by a lingering pale memory of "a love that should have lasted years." Good job, Paul McCartney! You've written a characteristically genius song which adds a nice emotional depth to the single best Beatles album.

Richard Furnstein: Much has been made of Alan Civil's French horn part in pedestrian Beatles writings. The facts are out there, and, yes, the guest solo is quite genius. In addition to providing another layer of British class to an already sterling song, the French horn manages to be both bubbly and burbling, suggesting a steady stream of tears. Our faces are left as damp as Mister Civil's spit valve. One imagines the distinguished horn player draining his instrument into an Abbey Road dustbin after his take as a group of moist eyes watch him from the control booth. Touched to be sure.

Tuesday, March 15, 2011

Eleanor Rigby

don't understand what has happened.

Richard Furnstein: What happened is the old reliable twentieth century of humankind and its unshakable desire to throw out the old and progress into a new age. We had electricity, flight, the atom bomb, Little Richard singing about forbidden pleasures, and then Paul decided to take the next huge leap with "Eleanor Rigby."It is pop music without the beat instruments, boneheaded lyrics, and overt sexuality. I take that back, it ain't even pop music. There's no real point in imagining the Beatles working through this song as a rock quartet. The recording is driven by a simplistic and creative string arrangement, while ignoring the crashing cymbals and other rock and roll conventions that drove their early albums. Listen to the strings push the verse melody. Listen to the unexpected force of the opening "aaaaaaaaah's." The acceleration in the middle of the verses is a perfect set up for Paul's reminder that these are lonely people. Your hearts should hurt...right....here. It may just be Paul's greatest story song. The characters are vivid and sympathetic: sketches of two lonely people, the title character (a crone who had everything but love) and the celibate Father McKenzie.

Robert Bunter: It's true. You're right. And not only did they do that, they also proved themselves, as ever, the masters of striking contrasts. Did you know that this was issued as a single with Yellow Submarine on the flip?

Richard Furnstein: Sure was, but I refuse to really acknowledge the singles that were taken from albums. "Paperback Writer" b/w "Rain" is the only Revolver-era single in my mind. So, you are wrong in my eyes.

Robert Bunter: Get over it, Rich. The point is, they went from the sublime to the ridiculous.

Richard Furnstein: Ringo delivered the knockout lyric here, describing the good Father MacKenzie "darning his socks in the night when there's nobody there." It's an absolutely beauty, and Mr. Starr doesn't received co-writer credits on this one. For shame, Lennon and McCartney! Give the drummer some.

Robert Bunter: Oh for Christ's sake.

Thursday, February 17, 2011

Love You To

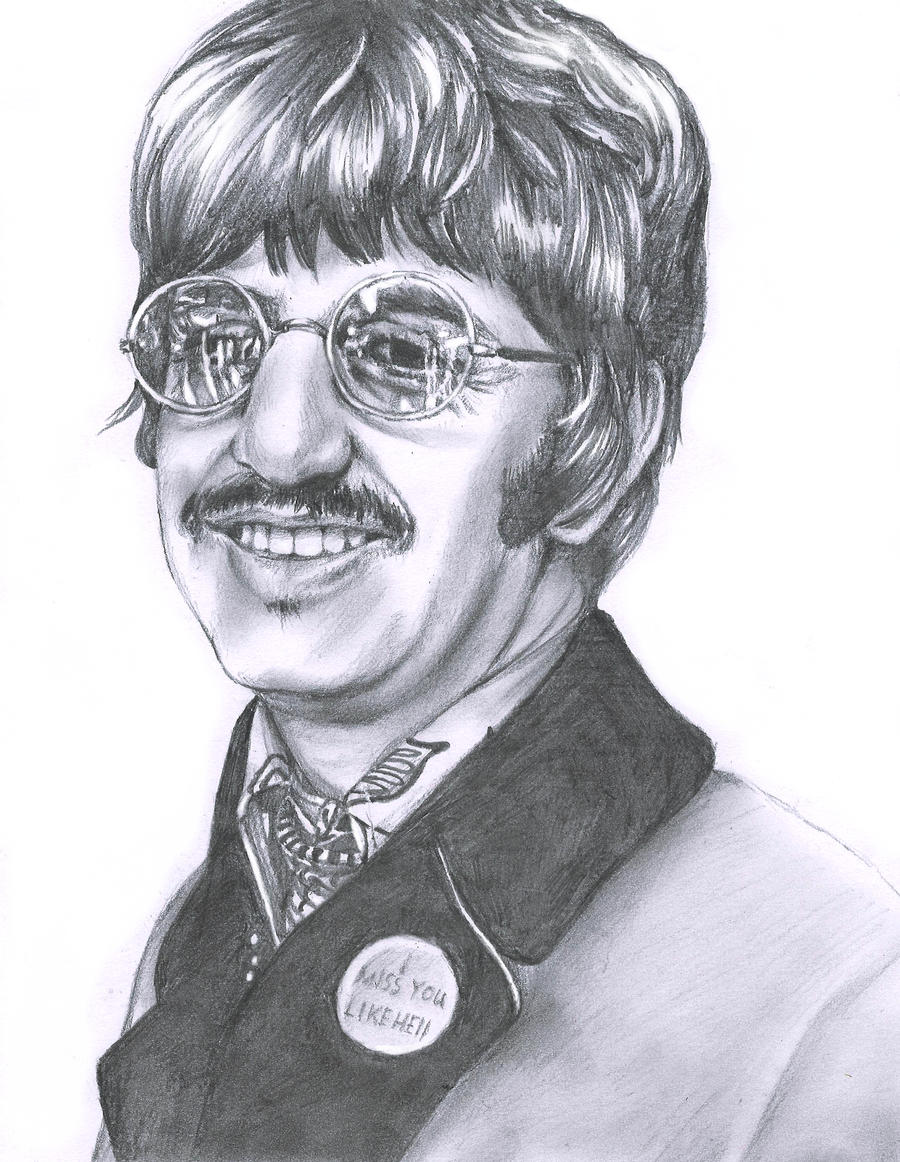

Robert Bunter: George takes another (his first) trip to the land of carpeted elephants and loosely-draped saris. The sitar on "Norwegian Wood" was just a toe-dip into the surging Ganges - now we're fully immersed. Fuzz bass meshes nicely with the sarods and spirit harps, and a double-tracked vocal (with McCartney chiming in on harmony) takes it to the next level. This one must have really blown every pimply kid's mind in 1966 when they got this back from the Woolworths and gave it a spin on their little plastic hi-fi. They called their friends immediately: "Hey, Chad! Did you get to the fourth song on side one yet? I think something's wrong with my hi-fi! I already frightened enough by Ringo's glasses on the back cover. I'm not ready for this!"

Robert Bunter: George takes another (his first) trip to the land of carpeted elephants and loosely-draped saris. The sitar on "Norwegian Wood" was just a toe-dip into the surging Ganges - now we're fully immersed. Fuzz bass meshes nicely with the sarods and spirit harps, and a double-tracked vocal (with McCartney chiming in on harmony) takes it to the next level. This one must have really blown every pimply kid's mind in 1966 when they got this back from the Woolworths and gave it a spin on their little plastic hi-fi. They called their friends immediately: "Hey, Chad! Did you get to the fourth song on side one yet? I think something's wrong with my hi-fi! I already frightened enough by Ringo's glasses on the back cover. I'm not ready for this!"