Richard Furnstein: An absolute and perfect work, “Strawberry Fields Forever” is the The Beatles at their best. It represents the peak of their songwriting craft, George Martin’s production and arrangement work, incidental and exciting floating instrumentation, and the unlimited creativity of the psychedelic era. Hell, I’d contend that it is the greatest creative work of the 20th Century. I feel weird dumping our typical giddy hyperbole on this masterpiece. Indeed, “Strawberry Fields Forever” has little connection to its only true sonic or songwriting antecedents (“Tomorrow Never Knows” and “In My Life,” respectively) as Lennon doesn’t reference or build on these prior works. Rather, he devises an entirely new language to tell the story of his brain. “Strawberry Fields Forever” is a completely unique animal; emerging tattered and strange from the ornate gardens of the mind. The song isn’t in the key of A; rather, it’s in the key of Air—a menacing and fragrant gas which disables the feeble human synapses and filters and resets the landscape below.

Robert Bunter: Yeah. It’s an altered mental state. The unfamiliar instruments (Mellotron and some kind of zingy Indian harp), the tapes played backwards or slowed down, the improbable yet beautiful chord changes, the trick ending – they not only illustrate the lyric’s precise yet vague portrait of confused uncertainty, they evoke and induce it. The listener can’t help but viscerally inhabit Lennon’s haunted mindspace. I don’t care how mentally together and emotionally secure you are, when you hear this song, you know what it feels like to be a rich, unhappy, drug-addled human genius full of pain from the past, fears for the future and disorientation in the present. Objectivity dissolves. Lennon was able to manufacture similarly hallucinogenic effects on his other two attempts at audio drugs (“I Am The Walrus” and the aforementioned “Tomorrow Never Knows”), but what elevates “Strawberry Fields Forever” is the beauty. It shines through the confusing textures like a warm smile inside of a nightmare.

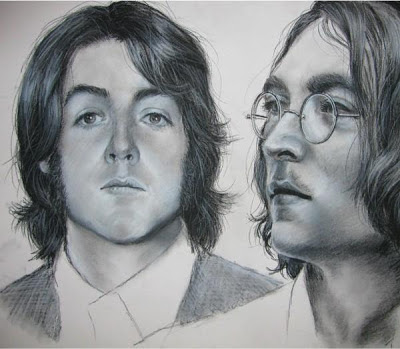

Richard Furnstein: The nightmare was certainly displayed in the promotional video for "Strawberry Fields Forever." The clip displays the band's new look--a combination of Victorian and lurid clothing, deviant facial hair, and the vacant, sad stares of internal psychedelic explorations. After an unheralded six months of creative chrysalis, they have emerged as underfed butterflies. There was nowhere to go but up: miles from the dull, patchy grass, through the pink smog, and into the pulsing light. Surprisingly, Paul McCartney is the most frightening figure in the video. His once friendly doe-eyes are lifeless (perhaps literally) and full of sorrow. Cloaked in a garish mustard-colored coat, he hops along the ground backwards and jumps into an expired oak tree. George and John have aged decades during their break from the public eye. Their gaunt bodies are hidden by technicolor fashions. Ringo looks the most familiar, but he is clearly searching for comfort in this strange world. The clip enters night during the slow, cello-drenched "no one I think is in my tree' verse. The tree is festooned with nylon spider web emerging from a piano. Is the tree fake? Is there truly nothing to get hung about in this caustic landscape? Ringo smiles with glee as they douse the piano in cans of paint. We (the viewers) are similarly baptized in these colorful new structures. Surely, everything that came before had to be scrapped as useless. This was it.

Robert Bunter: It wasn't just the video. The lyrics themselves are

addressed directly and personally from the John-figure to YOU, the

listener ("Let me take you down"), just like "I'd love to turn you on,"

"Isn't he a bit like you and me?", "Can you hear me?", "There's nothing

you can do that can't be done," "You can syndicate any boat you row" and

so many others, all the way back to "Oh yeah I tell you something / I

think you'll understand." This approach would come off has presumptuous

(at least) in the hands of a lesser artist, but John and the Beatles

were confidently aware that they occupied a special place in the

consciousness of their listeners. So, after a gracefully genteel Mellotron

prelude, the lyric begins with our old friend John disarmingly offering

to let us join him on a trip to Strawberry Fields. Informed fans know

that this was the name of an orphanage just around the corner from

John's childhood home in the Liverpool suburbs, where a young Lennon was

fond of listening to the sprightly tubas and cymbals of the Salvation

Army Band each summer at the annual garden party. One can even imagine

the domineering young lad rounding up his neighborhood chums on the way

to the fair by saying something like "Let me take you down 'cause I'm

going to Strawberry Field" in a cute little British accent. But

obviously John is working on a different level. He informs us that

"nothing is real" and, more alarmingly, "nothing to get hung about."

This casual, ho-hum attitude towards the existential riddles with which

John confronts us - "It doesn't matter much to me" - is almost as

terrifying as the cellos, reverse-time drum loops and old-man

moustaches.

Richard Furnstein: I beg to differ. John was not entreating the listener to take a "trip" down to the halcyon Strawberry Field. Instead, he was warning the listener that he was about to tell them the sad story of his shattered childhood ("let me take you

down"). It's significant that he set this alleged idealist piece of nostalgia in an orphanage as he was finally ready to tell the story of a mother who left him (and then suddenly died in a senseless accident as she decided she was finally ready to become a stable figure in his life) and an absentee seaman father. In "Strawberry Fields Forever," John envisions himself as a ward of the orphanage rather than merely a visitor to its lush gardens with his caretaker Aunt Mimi. John realizes that he is nothing more than an unwanted child, despite the best efforts of Aunt Mimi and Uncle George to create an illusion of stability and normalcy following his primal scream trauma (the loss of his parents). Indeed, "living is easy with eyes closed" suggests both John escape from his loss as he retreats to his rich and fractured imagination and Aunt Mimi's well-meaning illusion of a normal Liverpool family. Perhaps as an orphan, John could have realized a greater sense of connection to humanity ("no one I think is in my tree") in an age when traumatized children didn't receive psychiatric care. He was hiding his internal damage caused by the loss of his parents to the world rather than wearing his injuries proudly as a state-declared orphan. The casual mention of "nothing to get hung about" suggests that suicide is the only way to really stop the bleeding. John would be more emotionally direct in revealing his pain during his raw early solo years ("Mama don't go/Daddy come home" and "One thing you can't hide is when you're crippled inside"), as he finally received the therapy and time for self reflection that he desperately needed. However, the grace and poetry of the pain in "Strawberry Fields Forever" is somehow more startling than the grotesque exposure of those later lyrics.

Robert Bunter: The shattered childhood material is all there, but it’s

subtextual – indicated only by the title/refrain’s mention of an

orphanage and the track’s pairing with McCartney’s “Penny Lane” as an

explicitly two-sided meditation

on their shared Liverpool roots. The sad little chap, squinting

nearsightedly at the merry Salvation Army band and stoic war orphans of

early-‘50s England is now grown up. His already hyperactive

mental/emotional/spiritual Self has been rocketed to the highest

levels of wealth and artistic acclaim, then magnified and distorted

through his copious use of advanced pure mind drugs of the highest

pedigree. The Beatles just made the decision to stop touring and John,

at loose ends, decides to accept a minor movie role

and spend a few weeks filming in Spain. During the interminable waiting

periods between takes, he gently strums an acoustic guitar and ponders

the uncertain future of his career as a Beatle, his stultifying,

dead-end suburban family life with Cynthia and Julian,

and, yes, the bleak reality of his broken youth. The primal, crucial

questions of his life loom inescapably as he struggles to decipher their

answers through a haze of THC and boutique-quality lysergic acid. Am I a

madman or a genius? What is real and what

is illusion? How can I maintain my integrity and awareness in the face

of so much pain? It is startling to hear the John-figure -- so

accustomed to delivering pronouncements from on high, flashes of

righteous anger or cutting wit -- lost in melancholy confusion.

Who is this politely confused old man with the granny glasses and

moustache, singing “I think I know, I mean, ah yes, but”? Surely not the

same confident authority figure who had (quite recently) commanded us

all to turn off our minds, listen to the color

of our dreams and say the Word.

The beauty shines through the confusing textures like a warm smile inside of a nightmare.

Richard Furnstein: It's easy to imagine John languidly strumming this chord progression on the set of of How I Won The War. Literally and figuratively in a foxhole during the making of Richard Lester's dark comedy, Lennon was nervously awaiting the next development in his life. "Strawberry Fields Forever" was a bold and risky direction for the songwriter: he was exposing himself (emerging from the foxhole) to the rewards and risks of its creation. The glorious demos for "Strawberry Fields Forever" reveal the endless options of this strange composition. A Beatles fan could spend a decade in the stark and gentle productions of these early versions (combined and compiled nicely as part of the Beatles Anthology). Later in his life, Lennon claimed to be unhappy with odd patchwork of lushness and strangeness that was unleashed to the world like a psychedelic Frankenstein's Monster. You can almost understand his concerns because the final product--while pure brilliance--was so unusual and seemingly incongruent with his original vision of the song.

Robert Bunter: The story of how “Strawberry Fields Forever” was pieced together from wildly different takes in the studio is one of those Beatles stories that have been re-told in every book and documentary film, but I’ll briefly summarize it here. The song was first debuted to George Martin as a solo voice and acoustic guitar demo that George Martin later said was “utterly breathtaking” even in a completely unadorned state. Since it was the height of the studio experimentation phase, however, they clearly couldn’t let it go at that. John asked Martin to score the track for cellos and trumpets, and the resulting take was utterly striking and unique. John still wasn’t satisfied, however, and suggested they start from scratch with a more ponderous, heavy rock version that emphasized Ringo’s drums. This, too, was an artistic triumph. John still felt something was missing and asked Martin to join the two takes together. The staid, conservatory-trained producer nearly fell from his velvety-cushioned rotating studio chair with incredulity at Lennon’s inexhaustible naivete. “But John! They’re in completely different keys and tempos! What you’re asking is impossible!” But John just smiled and gave him “that look” and said, “Oh, I know you can do it, George” and floated away before his very eyes (actually, this was accomplished with a simple series of ropes and hidden pulleys arranged over the studio rafters by assistant Mal Evans and Ringo). Martin, suddenly alone in the cavernous studio space, racked his brain for several hours before he thought of the (totally obvious) idea to slow down the faster one a little bit and then speed up the slower one slightly. Miraculously, it worked – the keys and tempo matched perfectly. This is the reason John’s voice sounds more druggy and strange in the later verses. It may be difficult for a non-musician to understand just how startlingly unlikely it would be for that to work.

Richard Furnstein: John's voice also sounded more druggy because he was consuming Olympian doses of d-lysergic amid at the time. Martin's role was clearly to translate a madman's babbling for the Top 40; seducing happenstance with a surgeon's steady hand. Indeed, the studio trickery of the "Strawberry Fields Forever" master is more than mere psychedelic colouring (think of the BBC airwaves captured during the chaotic "I Am The Walrus" fade or the swarming clavioline that haunts "Baby, You're A Rich Man"). It is an essential element of Lennon's storytelling. He once implored us to "Listen to the colour of your dreams"--a nice enough sentiment--before taunting "It is not leaving." In other words, we have reached the point of no return. The dripping many-eyed iguanas and

undulating mindwave trails are here to stay. Are you

in or are

out?

Robert Bunter: I'm out. There's too much more to say, and we've already gone on too long. Maybe we'll do part two someday. Maybe. That would be a fine place to talk about the fake ending, the Mellotron, and the fact that this and "Penny Lane" were pulled from the Sgt. Pepper lineup as originally conceived. Let's get the hell out of here.

Richard Furnstein: Fair enough, old pal. This song is a burrito-as-big-as-your-head. Sometimes it is alright to get your fill and walk away.

We're all adults here.

Original Beatles fan art by Matthew Heisler